Crossings: Non-Privileged Migration and Mobility Control in the Age of Global Empires (c. 1850-1914).

Conference to be held at the German Historical Institute London, April 25-26, 2024

The time period between 1850 and 1914 is often referred to as the age of mass migration, with more than 30 million Europeans immigrating to the United States alone. However, as previous scholarship has shown, this was by no means an age of free movement. While overseas shipping routes expanded and prices in passenger transport fell, the period also saw increasing state interventions and the establishing of migration regimes that distinguished between “desirable” and “undesirable” immigrant groups. Although non-elite in social composition, the mass migration of the time was overwhelmingly a privileged “white” migration in the age of global empires.

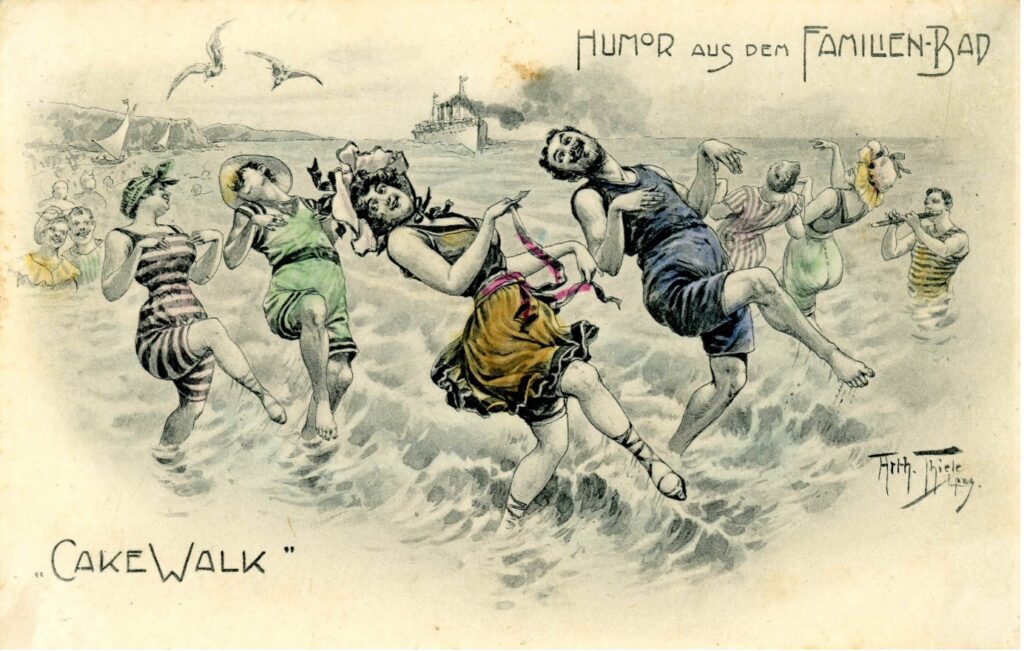

This is clear when we focus on groups whose transnational mobility was restricted or who were threatened with deportation. But neither state intervention nor societal hostility completely prevented groups labelled as “undesirable” from migrating – in flight from persecution and conflict or in search of opportunities to live and earn in another country. While adopting strategies of survival in the host countries, these groups of “undesired” immigrants often faced huge public responses, followed by new legislation and deportations, resulting in subsequent odysseys. This can be seen, for example, in colonial migration to Europe or in the Romani migration to the UK. Other groups remained under the radar, or only came into focus later, such as the Cape Verdean immigrants to the US.

This conference brings together research on non-privileged migration from the 1850s to the First World War. We invite contributions that explore transnational mobility and its restriction, emerging migration, citizenship and border regimes, economic strategies in “hostile environments” and the reconstruction, visualisation and memorialisation of migrants’ itineraries and experiences, including digital methods. We are especially interested in perspectives that combine (trans-)local with global and imperial perspectives. Contributions from all relevant disciplines are welcome.

Key questions include:

– How does a focus on non-privileged groups sharpen our understanding of transnational mobility and migration regimes in the age of global empires? Who became “undesirable” migrants, and what categories of social difference and their intersection took effect?

– What state interventions and policing practices were adopted? How did these differ between countries and empires, and what levels of international or transimperial cooperation were established? How did metropolitan and imperial migration regimes inform each other?

– What role did the media play in public responses to migration, and in how far were migrants and supporting groups able to use the media in their behalf?

– How did groups of migrants circumvent mobility restrictions, and what economic strategies did they adopt in the host countries, or post deportation? What was the role of private migration agents?

– With what methods can we reconstruct, make visible, and memorialise migrants’ itineraries and experiences?

The conference will be held at the German Historical Institute London (GHIL). It is co-financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), and the GHIL. We anticipate being able to reimburse standard travel expenses and the cost of accommodation for the duration of the conference. Papers from scholars at any stage of their career, drawing on developments in any world areas in the period roughly between 1850 and 1914 are invited. Abstracts of about 300 words and a short CV should be sent both to Felix Brahm and Eve Rosenhaft (felix.brahm@uni-muenster.de, dan85@liverpool.ac.uk) by 15.11.2023.

GHIL admin contact: Julian Triandafyllou (j.triandafyllou@ghil.ac.uk)